A long-ago, magical mile to remember

Scott, Walker, and Flynn ran race with world- and national-record implications in 1982

Four decades ago today, at roughly 5 p.m. Eastern time, American Steve Scott, New Zealander John Walker, and Irishman Ray Flynn toed the starting line for the men’s mile run in a meet at Bislett Stadium in Oslo.

The trio was part of a 10-runner field that had come to the Norwegian capital to run fast. No one was there to win a cautious, tactical race. The objective was to let it rip – with the help of a pacesetter – and let the chips fall where they may.

Little did they realize as young men – a band of brothers whose friendships developed over years racing and traveling together on the European track and field circuit – their performances that day would leave a mark amid a golden era of mile running and solidify Scott’s status as one of America’s greatest milers.

“I always had confidence running in Oslo,” Scott said. “It was like, okay, let’s go and we’re going to run a good time. And if you’re first, or second, or third, but if you got a lifetime best or a national record, that’s great. The concern about winning generally wasn’t as forefront on your mind. It was more like we’re gonna go out and we’re all going to race for a good time.”

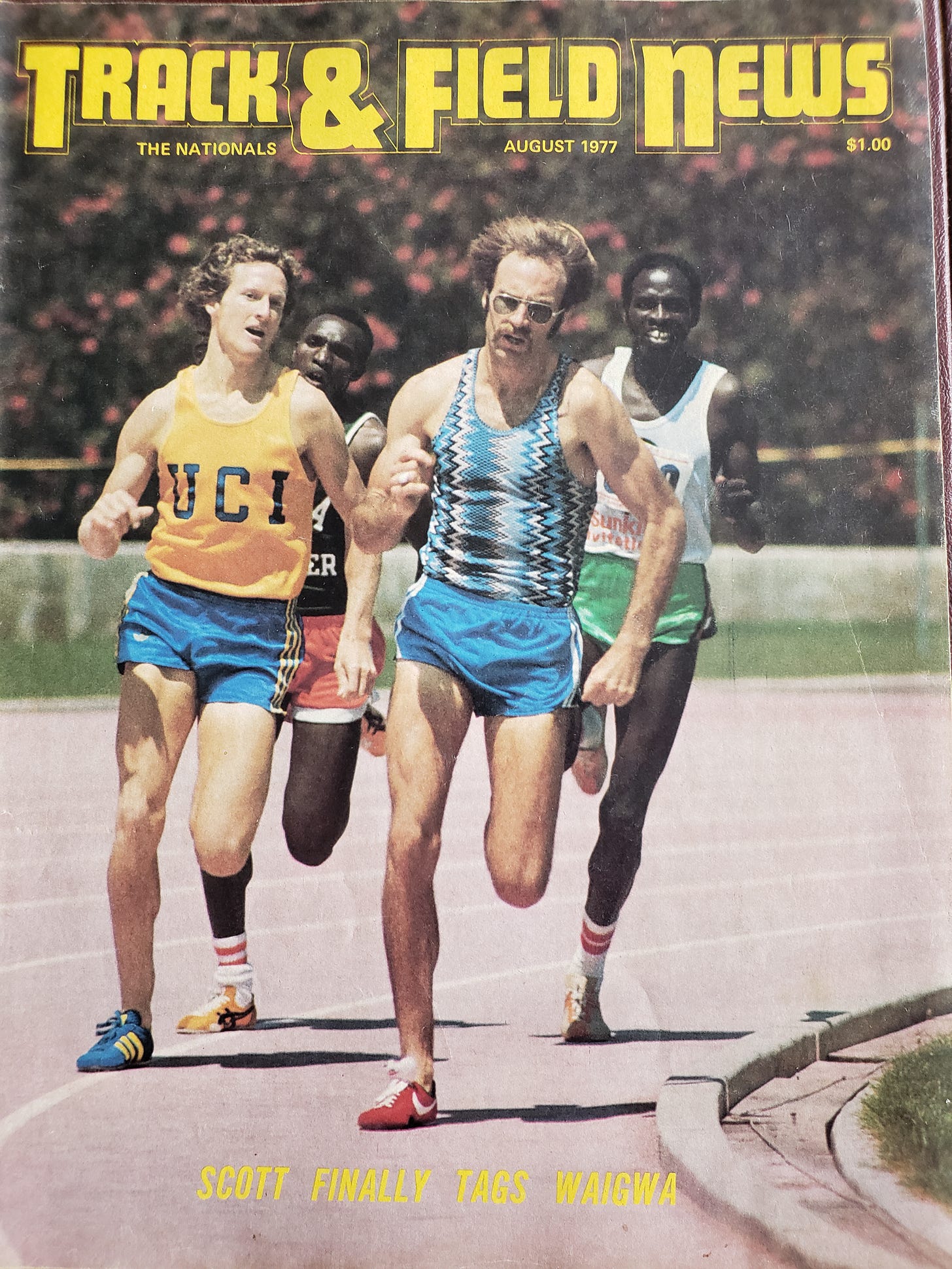

Scott was shooting for more than a good time, or even a national record that day. The graduate of UC Irvine in Southern California had his sights set on breaking the world record of 3 minutes 47.33 seconds that Sebastian Coe of Great Britain had run in the Van Damme Memorial meet in Brussels the previous August.

No American outside of two-time world-record setter Jim Ryun had seemed capable of seriously challenging the world record in the mile since the four-minute barrier had been broken in 1954.

Either Coe or countryman Steve Ovett had been the top-ranked 1,500-meter/mile runner in the world by Track & Field News from 1977-81 and they had combined to lower the world record in the mile five times from 1979-81, including three times during an incredible 10-day stretch in 1981 that was capped by Coe’s 3:47.33 clocking.

But with Coe injured and Ovett working his way back from an injury sustained during the winter, Scott was one of the milers who took center stage during the summer of 1982.

To fully appreciate the mindset of Scott, Walker, and Flynn as they prepared to race during that beautiful Scandinavian night in Oslo 40 years ago, it helps to know how they had come to that point in their careers.

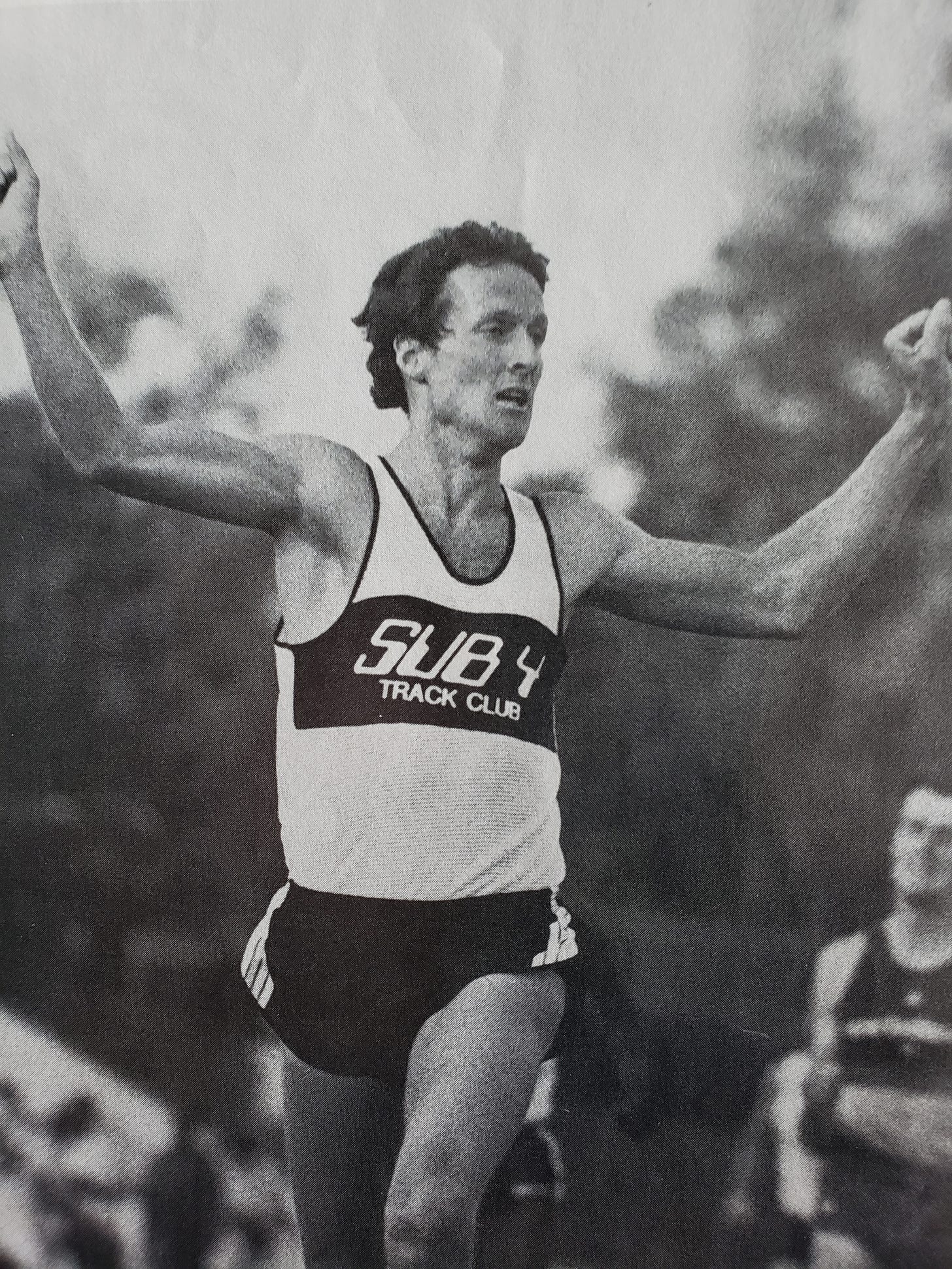

FROM PREP HALF-MILER TO AMERICAN RECORD-SETTING MILER

Scott had never run competitively until going out for cross-country as a freshman at Upland High School in Southern California in 1970 because he wanted to avoid gym class. And he didn’t run track until his junior year after he gave up baseball due to a lack of playing time.

Despite his late start, he ran 1:52.0 in the 880-yard run and 4:17.6 in the mile as a senior, and placed second in the 880 in the 1974 California state high school track and field championships.

Although Scott considered himself a half-miler, UC Irvine coach Len Miller told him during the recruiting process that he was going to be the next great American miler.

Scott laughed at the notion of specializing in the 1,500 meters and mile, but he won three consecutive NCAA Division II championships in the 1,500 from 1975-77 before winning the Division I title as a senior in 1978.

He says the 1976 U.S. Olympic Trials at the University of Oregon’s Hayward Field was a turning point in his career as Miller campaigned hard for him to be one of the three runners who were granted at-large berths in the 1,500 after they had failed to meet the automatic qualifying standard that 33 runners had met or bettered.

Despite his low ranking, Scott grabbed the last qualifying spot in the final, in which he finished seventh.

“Up until the summer of 76, if a coach was not standing over me, I was not training,” Scott admitted. “That all changed after going to the trials. It occurred to me that I didn’t deserve to be there. I didn’t have the dedication. I didn’t work like these other guys did. I basically challenged myself and wondered if I put in the training like they did, what can happen?”

He began running 70-80 miles a week that summer and garnered the first of eight consecutive No. 1 U.S. rankings after the 1977 season, when he ranked ninth globally.

He improved to a No. 7 world ranking in 1978 before making a big jump in 1979, when he ranked third globally and improved his personal bests to 3:34.6 in the 1,500 and 3:51.11 in the mile.

His mile best came in a race in Oslo in which he finished second to Coe, who ran 3:48.95 to break the world record of 3:49.4 that Walker had set in 1975.

The 1980 track and field season was an unusual one as the U.S. and more than 60 nations boycotted the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow to protest the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan.

Ovett had lowered the mile world record to 3:48.8 at a meet in Oslo on July 1 of that year, but he finished third behind Coe and Jurgen Straub of East Germany in the 1,500 in the Olympics after he had upset world-record holder Coe to win the 800.

After being ranked fourth in the world in 1980, Scott ran American records of 3:31.96 in the 1,500 and 3:49.68 in the mile in 1981. But those performances were overshadowed by the trio of world records in the mile set by Coe (3:48.53 on August 19), Ovett (3:48.40 on August 26), and Coe (3:47.33 on August 28).

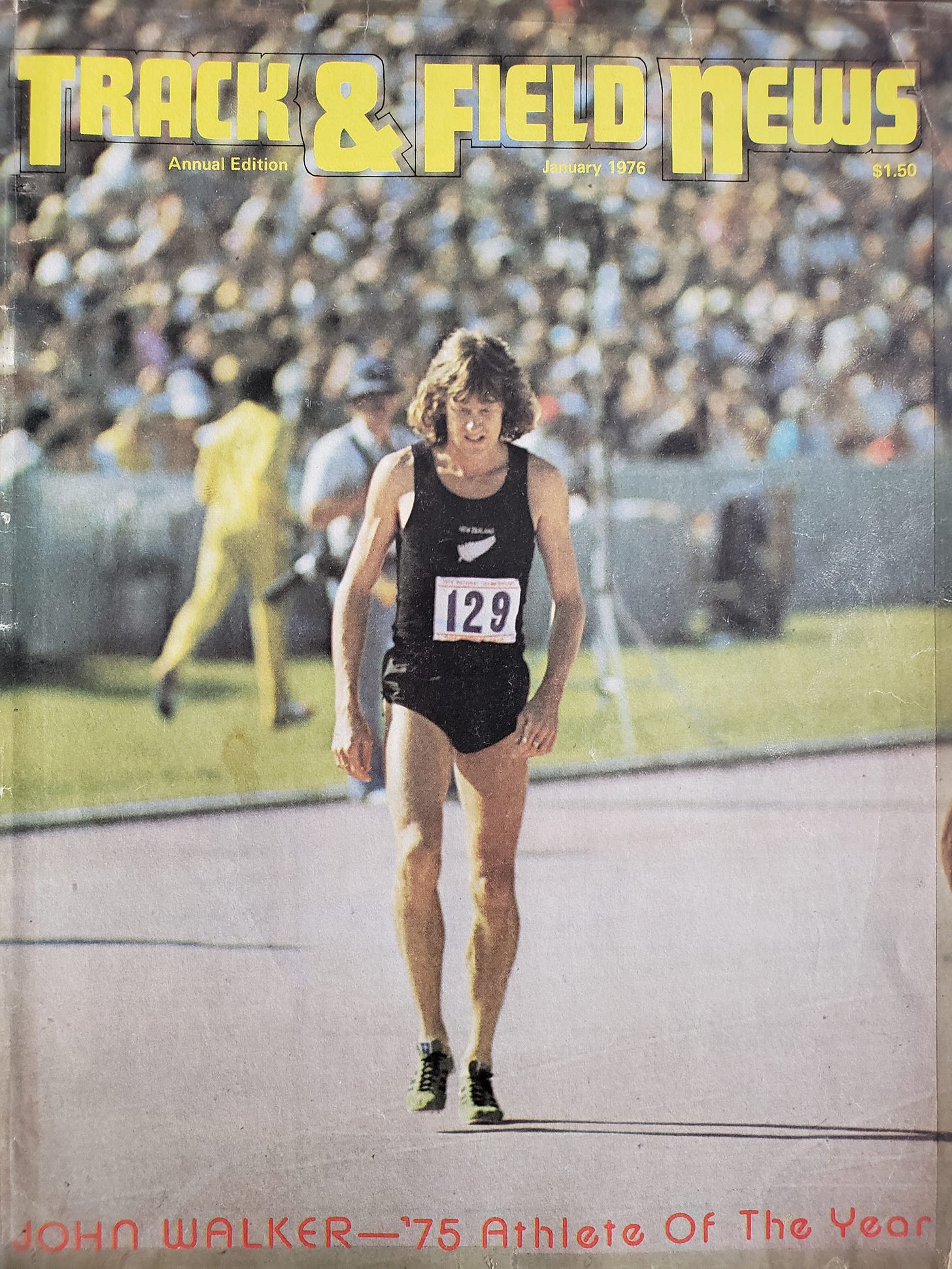

KIWI FLYER REBORN

Walker had been the world’s top-ranked 1,500 meter and mile runner from 1974-76.

He had burst onto the international scene in the British Commonwealth Games in Christchurch, New Zealand, in January of 1974 when he finished second to Filbert Bayi of Tanzania in the 1,500 meters in a race in which Bayi (3:32.16) and Walker (3:32.52) broke the previous world record of 3:33.1 set by Ryun in 1967.

He became the first man in history to break 3:50 in the mile in August of 1975 when he ran 3:49.4 in Goteborg, Sweden. He set a second world record in June of 1976 when he ran 4:51.52 in the 2,000 meters in Oslo – a performance he still calls his best ever – and then became the third New Zealand Olympic champion in the men’s 1,500 in the Games in Montreal at the end of July.

Although his string of No. 1 rankings ended in 1977, Walker was ranked third in the world behind Ovett and Thomas Wessinghage of West Germany.

He was not ranked among the top 10 performers in the world during the next two years as he dealt with leg issues in 1978. However, he bounced back to rank fifth in 1980 and sixth in 1981, when he ran what were then the second- and third-fastest miles of his life.

He entered 1982, during which he would turn 30, intent on running faster than he ever had.

LATE BLOOMER

Flynn, a native of Longford, Ireland, had finished eight hundredths of a second behind Scott in the 1,500 in the 1978 NCAA Championships as a senior at East Tennessee State, but his improvement had been more gradual than his contemporary during their first two post-collegiate years.

However, he lowered his mile best to 3:52.95 during the outdoor season in 1981 after running 3:53.8 indoors at a time when the world record of 3:52.6 was held by countryman Eamonn Coghlan.

He, like Scott and Walker, was focused on carrying the momentum he had generated during the 1981 season into 1982.

SETTING THE STAGE

Two races in particular laid the groundwork for Scott’s world-record attempt 40 years ago today.

The first race came in what was billed as The Dream Mile on June 26.

Held in Bislett Stadium, Scott outkicked Sydney Maree in a hotly-contested race to lower his American record to 3:48.53.

Maree, a South African native who had gained U.S. citizenship in 1981, finished second in 3:48.85, followed by David Moorcroft of Great Britain (3:49.34), Walker (3:49.50), Flynn (3:50.54), and John Gregorek of the U.S. (3:51.84).

It was the first race in history in which four men had run under 3:50.

Track & Field News reported that the top six finishers battled around the final turn before Scott stepped on the accelerator in the final home straightaway to edge past Maree.

“It wasn’t an easy race,” Scott said afterward. “Sydney really put the pressure on and I didn’t expect so many people to be up front fighting for the win with 200 to go. I stayed in the pack because in the past people would cut me off just when I tried to move up. I would have liked to have been leading with a 200 to go, but I had to come from too far back.”

The second race came eight days later, on July 4, when Scott ran a personal best of 1:45.05 to win the 800 in a meet in the Norwegian village of Byrkjelo. Walker, who ran 1:45.59 to finish second, told Scott afterward that he was primed to break the world record in the mile in the meet in Oslo that was three days away.

“He said, ‘You’re ready,’ “ Scott recalled. “He told me that I had just run the best 800 of my life after running 3:48 in the mile. So he was the one who put it in my ear that I could do it. I owe him a lot because that was a big confidence builder. He knew what to look for so him saying that meant a lot to me.”

While Scott approached the upcoming race with the world record on his mind, Walker was intent on bettering his 3:49.4 personal best that had been the world record back in 1975. Flynn knew that the upcoming race was a great opportunity to become the first Irishman to break 3:50 in the mile.

“We had all raced in Oslo two weeks earlier with good results so the expectations were high,” he said. “Coming off the success of the previous race, and running in Bislett Stadium, which was sort of the mecca for distance running, we all went there with expectations to run our best races ever.”

The Oslo track had been the site of a slew of world records at that point, including Belgian Roger Moens’ 1:45.7 clocking in the 800 in 1955, Australian Ron Clarke’s 27:39.4 in the 10,000 in 1965, Swede Anders Garderud’s 8:10.4 in the 3,000-meter steeplechase in 1975, and Kenyan Henry Rono’s 7:32.1 in the 3,000 in 1978.

“If there was ever a meet in Oslo, I wanted to be there,” Scott said. “That was always my favorite track and favorite crowd. The track was smaller back then. It was six lanes and the fans were really right on top of you. Even if it wasn’t a full house, it always seemed like it was a full house. They had the signs along the side of the track and the fans were pounding on them as you went around. It was like thunder.”

Walker said racing in Bislett Stadium was magical.

“You knew it was a very fast track and you knew you were going to run fast,” he said. “You got energy from the crowd because they were really close to you and they knew a lot about the mile. The crowd gave you energy and you wanted to give them what they wanted.”

The weather was usually clear and balmy and the mile was typically run late at night, local time, so it could be shown live during the afternoon in the U.S. on ABC’s Wide World of Sports.

“There wasn’t any heat. There wasn’t any wind,” Scott said. “Typically, it had rained earlier. So it just seemed like the air was full of oxygen. The weather was always great and the field was always great. On that particular night, we had a great rabbit who just set a perfect pace.”

The rabbit, or pacesetter, was American Mark Fricker.

He moved into the lead halfway down the first backstretch and clocked 56 seconds after the first quarter-mile and 1:52.7 at the 880-yard mark. Walker, Scott, and Flynn followed in that order, with Flynn having an eight-meter advantage over the next closest runner, Australian Michael Hillardt.

Fricker continued to lead until midway through the second turn on the third lap, when Walker, Scott, and Flynn swept past him.

Walker still led when he passed through three-quarters of a mile in 2:51.5, but Scott was running just off of his right shoulder, looking very relaxed and full of run.

The 6-foot-1, 165-pound Scott surged into the lead entering the backstretch and he soon opened up a two-stride lead on Walker, who was passed by Flynn with about 240 yards left in the race.

Walker began to make up ground on Flynn midway through the turn, but there was no catching Scott, who entered the home straightaway with a lead of seven or eight yards that he had widened substantially when he crossed the finish line in 3:47.69, the second fastest time in history, a paltry .36 seconds shy of the world record.

Walker finished second in a New Zealand record of 3:49.08 and Flynn placed third in an Irish record of 3:49.77 to move to fifth and ninth, respectively, on the all-time world performer list.

“I think if [Steve] had gone by me with 400 meters to go, he would have set the world record,” Walker said.

Despite what Scott said about running for time when racing in Oslo, he admitted he hesitated when he had the opportunity to pass Walker with a lap to go.

“So I went wide around the turn and passed him on the backstretch,” he said. “The reason I didn’t take off earlier was I didn’t want to tie up and have John beat me because you could never count out John Walker. He was as tough as nails and he was competitive. You know, he’s four years older than me, but that didn’t make a difference.”

Scott realized he could have made an earlier move shortly after crossing the finish line.

“At the finish, I wasn’t tying up at all,” he said. “Not in the last 100, not in the last 50, not in the last 25. Usually if you have the pedal to the metal and you’re giving it all you’ve got, you’re going to tie up, and that’s the whole objective of racing is to give it your all so at the very end, like the last 10 meters of the race, you’re tying up. I wasn’t tying up. I crossed the finish line and I wasn’t doubled over and totally spent. So I could have moved quite a bit earlier, and had enough left and run quite a bit faster. But you know, woulda, shoulda, coulda.”

In contrast to Scott, Walker and Flynn were both exhausted after finishing with times that still stand as the national records for New Zealand and Ireland.

“The last 50 meters, I was buggered,” Walker said. “I was really tired the last 50 meters of the race.”

Flynn had put forth such an effort that he vomited afterward.

“I remember a lot about that night,” he said. “I remember throwing up on the side of the track because I really didn’t have anything left. I remember us jogging back up to where we were staying. It was like one o’clock in the morning, and I remember looking up and thinking it could be the middle of the day because it was still so light out at that time of the year in Norway.”

Flynn also remembers watching Moorcroft crush the world record in the 5,000 meters shortly after Scott’s narrow miss in the mile.

Moorcroft was so far ahead of world record pace during his 13:00.42 performance that with a lap to go he knew he was going to break the record of 13:06.20 that Rono set 10 months earlier.

Although Scott would go on to win a silver medal in the 1,500 meters in the inaugural World Championships in Helsinki in 1983, and place 10th and 5th, respectively, in the 1984 and ’88 Olympics, he never surpassed his 3:47.69 clocking in the mile, which stood as the American record until Alan Webb ran 3:46.91 in 2007.

Scott, who ran an unprecedented 137 sub-four-minute miles during his career, said he used to recall the race every July 7 until Webb broke his record.

Walker, who ran 135 sub-four-minute miles, said July 7 has never been anything special to him because the competition “was just another race.”

But Flynn, a two-time Olympian, said he will always view July 7 as a special day.

“I was pretty much to my top end what I did that night,” he said. “That was a magnificent run for me. I think we were all running to the best of our abilities.”

Although Steve Cram of Great Britain would break Coe’s world record with a 3:46.32 clocking in 1985, the 1981 and 1982 seasons were magical ones in the mile as the 3:50 barrier was broken a combined 23 times during those two years. Prior to that, it had been broken a total of four times.

Flynn says he hopes Scott will always remember that race with fondness.

“He may be the most consistent miler in history,” Flynn said of Scott. “That race was definitely the culmination of all those races. So even though his time was beaten by Alan, that doesn’t take anything away from it. That race was an incredible marker. And I am thinking a lot about it these days.”

TIME WAITS FOR NO ONE

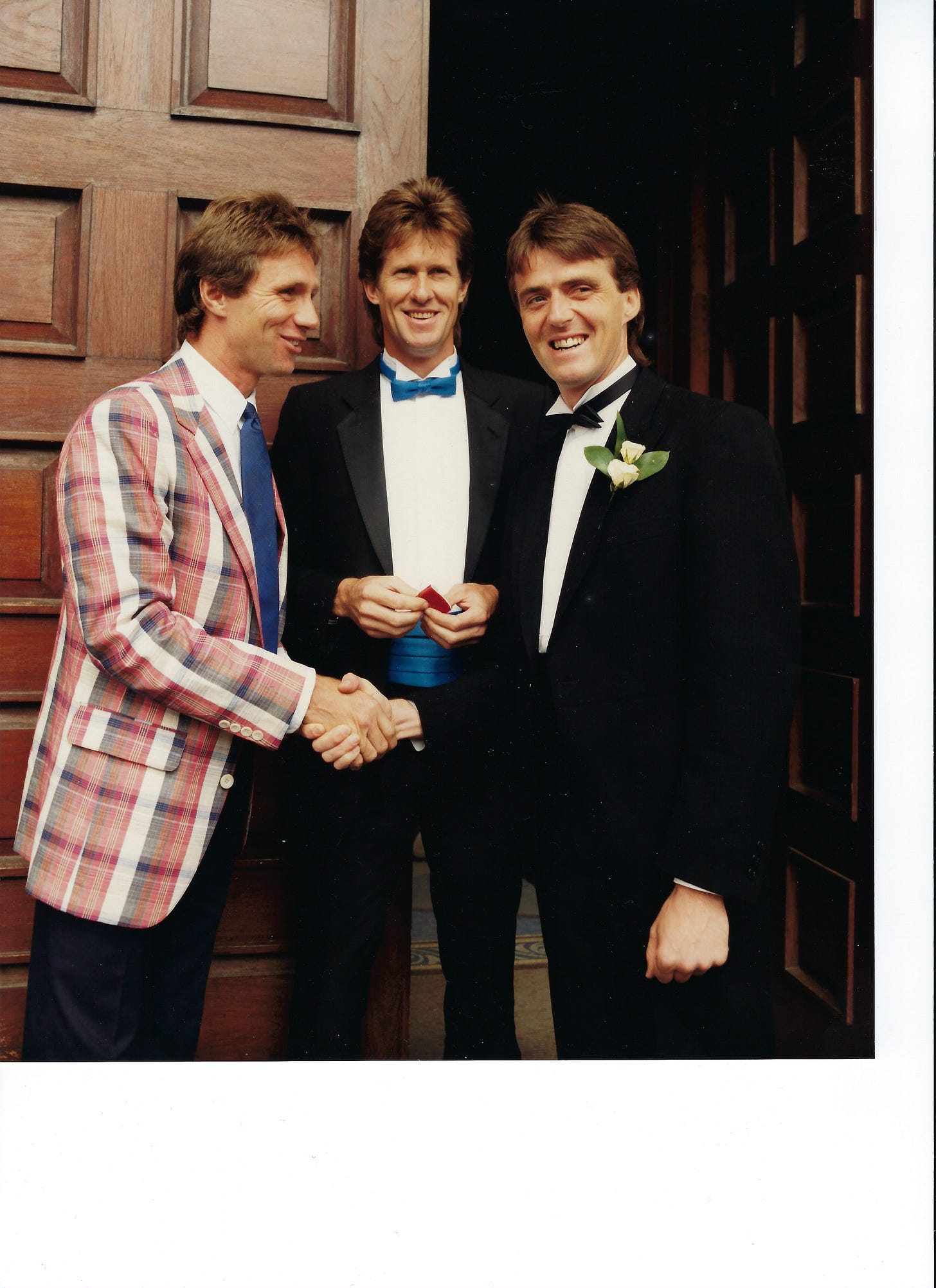

A lot has happened in the lives of Steve Scott, John Walker, and Ray Flynn since that memorable night in Oslo 40 years ago.

All three of them ran competitively for many more years with Flynn retiring in 1990, Walker in 1991, and Scott in 1997.

Walker was the best man at Flynn’s wedding in 1986, his wife Helen was in the wedding party, and their two oldest children, Elizabeth and Richard, were ring bearers.

Scott, Walker, and Flynn are all grandparents, and Scott was a highly successful cross-country and track and field coach at California State University San Marcos from 1999-2018.

The Walkers own a business called Stirrups Equestrian in Auckland, New Zealand, and Helen and youngest daughter Caitlin are involved in the everyday operations.

John, who was a councillor for the merged Auckland Council from 2010-19, worked at the business for many years, but he no longer does so as he deals with the effects of Parkinson’s disease.

He was diagnosed with the disease in 1996, but Helen wrote in an email that he is “coping well… and is still managing to do things, including exercise. It is an ongoing challenge.”

Scott, who lives in Lake Kiowa, Texas, with his wife JoAnn and their poodle, Willa, plays golf twice a week and attends bible study another day. He enjoys spending time working in the yard and exercises regularly.

There are some days when he has nothing planned and he is fine with that. He has learned to slow down as he has grown older as he has dealt with testicular and prostate cancer, a pulmonary embolism, and atrial fibrillation since the mid-1990s.

Flynn has been the president and CEO of Flynn Sports Management in Gray, Tennessee, since founding the company in 1989.

He loves interacting with track and field athletes and helping them succeed in their careers, but wishes more of them knew about the history of their sport.

An incredibly well-written article; thank you for taking me there. I have always been a fan of John Walker's and in more general terms, that era of miling (and other middle distances) from the mid-70s through the mid-80s. This article greatly adds to my fascination with that time period and the athletes who seemed larger than life.

Fantastic article of an amazing race, and era. I appreciate it very much. Thank you. I look forward to subscribing to your newsletter, and will do so shortly once at my office computer. Ovett/ Coe was such a media phenomena then (very appropriately)…. And many fans came to regard them as racers from another planet. When Scott ran such a fast mile that night, I remember being totally stunned!