Stanley joins L.A. City Section elite

Granada Hills junior is fastest quarter-miler in section since 2005

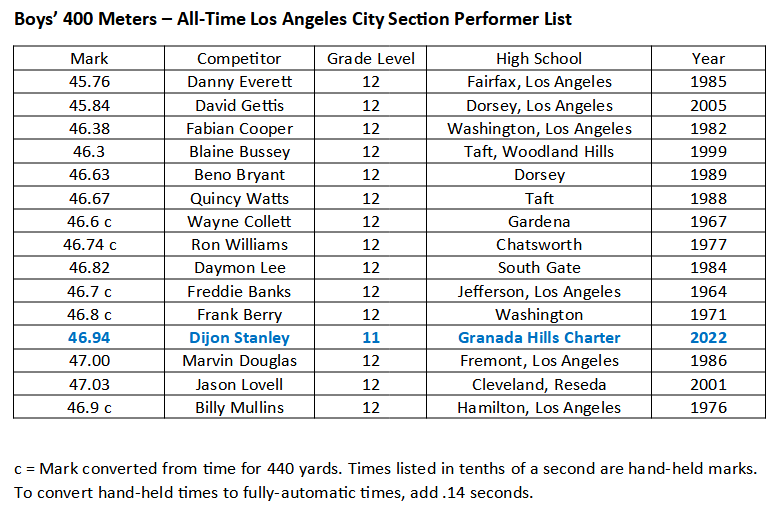

Danny Everett. David Gettis. Quincy Watts. Wayne Collett.

Dijon Stanley of Granada Hills Charter is getting familiar with other names on the all-time Los Angeles City Section list now that he has joined it.

The Highlander junior became one of the dozen fastest 400-meter sprinters in section history by running a school record of 46.94 seconds in the City track and field championships at Birmingham High School in Lake Balboa last week.

The time was the fastest by a City Section athlete since Gettis ran 45.84 in 2005 to win an unprecedented third consecutive one-lap title for Dorsey High of Los Angeles in the CIF state track and field championships.

After running for a Southern Section school as a freshman, Stanley said it’s “very important” to him now to be a standard bearer for the City Section, which has experienced minimal success at the state level in recent years.

“I know how people view the city,” said Stanley, who transferred from Grace Brethren in Simi Valley two years ago. “I know how people talk about it. And a lot of people say it’s very much watered-down. I used to train with some of those people and they let me know all the time that I have it easy. I actually feel that a lot of people, not just me, have brought the City to light this season.”

In addition to his victory in the 400, Stanley also won the 200, and ran legs on the winning 400 and 1,600 relay teams in the section finals to lead Granada Hills to its first team title.

Terrell Stanley, Dijon’s father and an assistant coach at Granada Hills, does not expect Dijon to run in a qualifying heat of 1,600 relay when the state championships begin at Buchanan High in Clovis today, but he will compete in heats of the 400 relay, 400, and 200, in that order.

“I was going to try to get him to run just the 4 by 1 and the 400,” Terrell said. “But he wants to run the 200. He wants to see a fast time in that event so we’ll see what happens.”

The 6-foot-1, 175-pound Stanley is the No. 2 entry in the 400 and he and teammates Jordan Coleman, Jeremy Gamble, and Jayden Smith have the third-fastest qualifying time in the 400 relay at 41.34, but he is ranked 10th in the 200. However, he wants to see what he can do while running in a heat that includes Jeremiah Walker of Central High in Fresno, who has run 20.89 this season.

“I’m praying for a sub-21 time,” said Stanley, who ran 21.53 to win the City title. “But if I can run 21.00 or 21.10, that would be great.”

If things go well today, when the state championships will be held for the first time since 2019 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Stanley will run in the finals of the 400 relay at 6:05 p.m., Pacific time, on Saturday, followed by the 400 at 7:00, and the 200 at 8:30.

“There’s more there; we can go faster,” Terrell Stanley said about the 400. “We’ve been trying a few strategies. So I think we’ve connected with what we want to do and I think we’re going to go a little faster than 46.9. We will have to go faster to win the race.”

Senior Christopher Goode of West Ranch High in Stevenson Ranch is favored in the boys’ 400 after he ran a yearly state-leading time of 46.75 in the Southern Section Masters Meet last Saturday. But Dijon expects a tightly-contested race in the final.

“There’s a lot of guys that have been running a lot of the same times,” he said. “We’ve raced each other more than once and we have all been very close. So yeah, the race should be great.”

“I know how people view the City. I know how people talk about it.” — Dijon Stanley, standout City Section quarter-miler

In addition to Goode and Stanley, Walker has run 47.27 this season, followed by Logan Davis of Marshall Fundamental in Pasadena and Adren Parker of Helix High in La Mesa, who have both run 47.31.

Christopher Coats of Upland finished fifth in 47.77 in the Masters Meet, but he ran a personal best of 47.42 to defeat Parker (47.70) and Stanley (47.74) in the Mt. San Antonio College Relays on April 16.

Stanley placed second in the invitational race of the Arcadia Invitational a week before that with a then-personal best of 47.26 to finish ahead of third-place Parker (47.36) and seventh-place Coats (47.78).

While Stanley is leery of focusing too much on his fellow competitors, the highly-touted football running back likes to know their tendencies.

“It’s probably because I play football, but I like to study my opponents,” he said. “So when I get into the race, I have my own strategy, but I also know what they’re going to do. That way, they don’t catch me off guard.”

Stanley, who takes pride in excelling in the classroom as well as in athletics, said confidence and a strong finish are his greatest assets in the 400. His dad adds he has the ability to run within himself down the backstretch of the 400.

“He gets real calm and relaxed,” Terrell said. “I think a lot of 400 sprinters get taken by surprise when he runs up on them. They feel like they’re running fast and when he comes up on them, it breaks their strategy because he’s right next to them.”

When asked to break down how Dijon runs the 400, Terrell said he gets out hard for the first 150 meters, then glides or floats the next 100, before working on the final 150 and finishing strong. Dijon said he usually changes his cadence midway through the second curve when he passes by where the scoreboard is located on most tracks.

“When I get into that last 100, I just push as hard as I can,” he said. “Because when a lot of people get off the track, they’re like, Oh, I wish I did this better. Or, I wish I did that better. After you get off the track, you really can’t do anything about it so you need to leave it all out there.”

While Gettis is the last City Section athlete to win the boys’ 400 in the state meet, three individuals who rank ahead of Stanley on the all-time list – Fred Banks of Jefferson in Los Angeles in 1964, Beno Bryant of Dorsey in 1989, and Fabian Cooper of Washington in Los Angeles in 1999 – also won state titles.

Everett, who ran a still-standing section record of 45.76 for Fairfax High in Los Angeles in 1985; Watts, who ran 46.67 for Taft High in Woodland Hills in 1988, and Collett, who ran a hand-held time of 46.9 in the 440-yard dash for Gardena High in 1967, did not win one-lap titles in the state championships. But they went on to perform superbly at the national and international level.

Everett was the bronze medalist in the 400 in the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul and ran a career best of 43.81 in winning the event in the 1992 U.S. Olympic Trials. An injury slowed him in the Games in Barcelona later that summer, but Watts set a pair of Olympic records in the 400 in those Olympics, and won the final in a career best of 43.50.

Collett, who passed away in 2010, was the silver medalist in the 400 in the 1972 Olympics in Munich, and had a career best of 44.1.

Everett, Watts, and Collett excelled on the international stage because they were able to stay composed while competing in high-level competitions.

Stanley has improved greatly in that regard this year.

“Sometimes when I’m running, I can get psyched out of a race when the meets are bigger,” he said. “It’s not a very good way to be, but it has happened. It’s something I do need to work on and which I have improved on this season.”

Terrell is confident Dijon will run well in the state meet because he performed well in competitions such as the Arcadia Invitational and Mt. SAC Relays this year.

As he puts it, Dijon has “been on more bigger stages this year.” He’s run in a lot more invitationals this year than last year, and that has put him more at ease in the larger meets.

Dijon is also learning to not overthink things when it comes to high-level races.

“I feel like sometimes I can think a lot about the little stuff,” he said. “And my dad has told me, ‘It’s just a race. Win, lose, or draw, you get off the track, and it’s over.’”

Terrell adds, “It’s not a boxing match. We’re not going into a fight with Floyd Mayweather, so you’re okay. You’re going to walk away from this fine.”

Even so, the 400 is never easy.

“When you get off the track, your head hurts, and your body hurts,” Dijon said of the longest sprint race. “Running the other sprints, you get off the track, you’re fine. You catch a little air and you’ll be fine. But after the 400, it’s a whole different thing.”

Not that he is intimidated by the post-race pain he knows is coming after he’s run a good one.

“The 400 is not for the weak,” he said. “When you finish the race, you want to feel like you left it all out there and you couldn’t give any more. I want to be crying. I want to be tired.”