Call it tough love, a reality check, or telling it like it is.

The time had come for Shawn Proffitt to speak with Donald Scott about his chances of playing in the NFL.

Proffitt had become a father figure to Scott while coaching him during track and field season at Apopka High School in Florida and knew he aspired to play wide receiver on Sundays.

He didn’t want to squash that dream out of hand, but figured Scott, a senior-to-be at Eastern Michigan University, had the athletic ability to become a world-class triple jumper if he focused on the event full-time.

“I told him he would have to have at least 700 or 800 yards as a receiver before any scouts would look at him” Proffitt recalled. “He said something like, ‘I have that many yards.’ And I said, ‘Not career yards. Yards in a season.’ “

Fast forward eight years and Scott will open his outdoor track and field campaign at the Tom Jones Invitational at the University of Florida on Saturday, four weeks after winning a bronze medal in the men’s triple jump in the World Athletics Indoor Championships in Belgrade, Serbia.

“It was very important,” Scott said of that performance. “It was my first world medal and winning one was a goal of mine leading up to the World Championships later this year.”

It would be incorrect to say Proffitt’s heart-to-heart talk with Scott led him to immediately nix his desire to play in the NFL. But at some point he approached his track and field coaches at EMU with the idea of redshirting the 2014 outdoor season so he could train for the triple jump during the fall, something he had been unable to do when he was playing football for the Eagles.

“I was thrilled that was what he wanted,” said Sterling Roberts, who started at EMU as an assistant coach during the 2012-13 academic year. “The amount of advancement and development he made as a senior was incredible.”

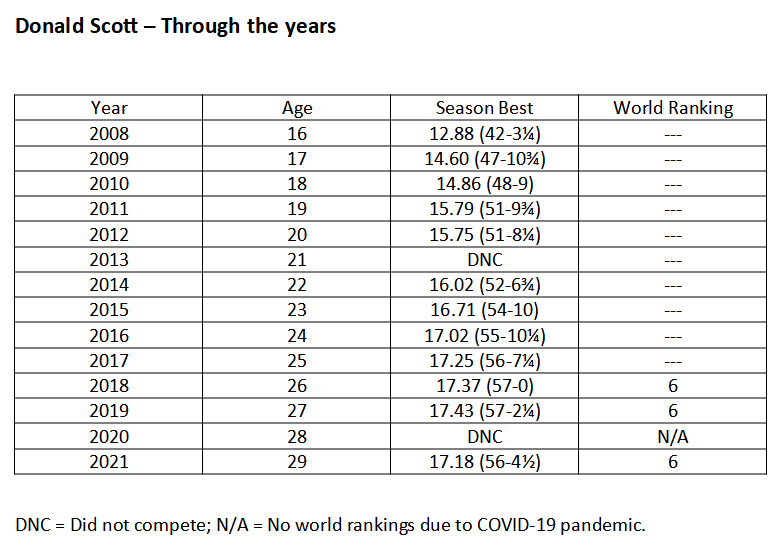

Scott lengthened his outdoor personal best from 16.02 meters (52 feet 6¾ inches) in 2014 to 16.71 (54-10) in 2015, and placed second and third, respectively, in the NCAA indoor and outdoor championships.

“He improved a lot,” Roberts said. “And I think his attitude was, I did all this with one year of training.”

Said Scott, “I didn’t have the greatest football career in college. It’s like track definitely grew on me because I was in the mix. You know, one of the top jumpers in the nation and things like that. So why not go ahead and transfer over from football to track.”

Although Scott placed sixth in the 2019 World Championships in Doha, Qatar, and seventh in the Olympic Games in Tokyo last summer, he still has plenty to learn about an event that is sometimes referred to as the hop, step and jump. That term makes the triple jump sound simple, but it is a technically challenging event.

In layman’s terms, there is the approach phase of the triple jump, when the athlete sprints down the runaway in an effort to hit the take-off board with a maximum amount of speed, followed by the hop phase, the step phase, and the jump phase. And the hop, step, and jump phases each have a beginning, middle and end.

“We tend to break down each phase and then how to put them all together,” Scott said of his training. “So we focus on the hop phase. And then it’s on to the step phase, and then on to the jump, and how to finish it.”

If excelling in the triple jump sounds complicated, it’s because it is.

Proffitt says the 10,000-hour rule – that one does not become an expert in any endeavor until they have 10,000 hours of experience in it – definitely applies to the triple jump.

Roberts, who continues to coach Scott, and Proffitt both describe him as someone who can be quiet during training but is always listening to what you are saying.

“He was very coachable,” Proffitt said. “He did not talk a lot, but you could tell he was listening. And he would come back later and ask you a question about something you had said. I talked to him, not at him. He didn’t feel like he had to answer every time I said something.”

Said Roberts, “He’s a quiet young man. He’s very kind of soft-spoken, but all business. … He wasn’t a big talker in college. It was always business, but you could tell that he cared.”

Scott, 30, calls himself an introvert and acknowledges he kept to himself a lot as a child while spending time in foster care, separate from his three older sisters. The four of them were adopted by an uncle – his mom’s brother – and aunt when he was 11 or 12.

He does not go into detail about what led to him and his sisters being put in the foster care system, but says neglect and abuse were factors. He says his mom was “in and out” of his life, and he did not meet his dad until he was 11.

His mom died in 2019, shortly before Scott headed to the World Championships in Doha. But he speaks with his dad on a monthly basis and says their relationship really began to develop when he was at EMU.

“When it comes to accomplishing something. I’m definitely determined and a driven person for sure,” Scott said. “I had a lot of adversity, but came a long way. I just use that to keep me going and I just have a lot of goals that I want to complete.”

One of those goals is to qualify for the U.S. team that will compete in the World Championships in Eugene, Oregon, from July 15-24. A second is to win a medal once there. A third is to compete through at least the end of the 2025 season.

Roberts figures all of those goals are achievable, as long as Scott does not try to be someone he’s not.

“He’s Donald Scott so he needs to jump like Donald Scott,” Roberts said. “He’s not Christian Taylor. He’s not Jonathan Edwards. He’s not Willie Banks. So he should not try to jump like them.”

Taylor, Edwards and Banks have all played significant roles in the history of the men’s triple jump.

Taylor was the top-ranked performer in the world by Track & Field News seven times from 2011-19 and was favored to win a record-tying third consecutive Olympic title in the event in Tokyo before he ruptured his right Achilles’ tendon while competing in the Ostrava Golden Spike meet in the Czech Republic last May.

Edwards, of the United Kingdom, was ranked first seven times from 1995-2002 and set three world records during his magical 1995 season that saw him set world records of 18.16 (59-6¾) and 18.29 (60-0) on his first and second jumps of the final of the World Championships in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Banks set a world record of 17.97 (58-11¼) in the USA Track & Field Championships in Indianapolis in June of 1985 that lasted until Edwards bounded 17.98 (58-11¾) in Salamanca, Spain, in July of 1995.

Taylor, who has the second longest jump in history at 18.21 (59-9), is known for his speed on the runway. Scott is known as a power jumper.

“His strength is his strength,” Roberts said of Scott. “He is stronger than just about anyone else out there. His biggest weakness is he’s not fast for a world-class athlete… When I first started working with him, he ran like a football player, kind of hunched over at the shoulders and looking like he was going to make a cut somewhere. We want to amplify his power, but nurture his speed to make him as fast as we can on runway.”

Proffitt, one of the top prep steeplechasers in the nation as a senior at Anderson High School in Cincinnati in 1988, would like to claim his keen eye for talent pegged Scott as a triple jumper from the get go.

But he was training him as a hurdler – Scott wanted to be a sprinter – before having an epiphany one day when they were walking over to train on a field next to the high school’s football field and track, and his charge took two or three short steps before bounding over a water retention area that was at least 15 feet across.

“He cleared it easily,” Proffitt said. “I had him competing in the long and triple jump within a week or two.”

That 2007 track and field season launched a relationship between Proffitt and Scott that has gradually strengthened over time.

Proffitt refers to Scott as a son and a brother to his two daughters, one of whom is a junior at the University of Cincinnati and another who is a high school senior headed to the University of Kentucky.

Scott frequently spends major holidays with the Proffitt family, and refers to Shawn as a “father figure to this day.”

He adds Proffitt introduced him to the basics of the triple jump and from there he just got better.

Despite his strength and athleticism, Scott was not an overnight sensation in the triple jump in high school.

He jumped 12.88 (42-3¼) as a sophomore before improving to 14.60 (47-10¾) as a junior and 14.86 (48-9) as a senior. Although he came to EMU on a football scholarship, it was agreed he would be allowed to compete in track in the spring.

That turned out to be fortuitous as he has won the last three USA Track & Field indoor titles, has career bests of 17.24 (56-6¾) indoors and 17.43 (57-2¼) outdoors, and has had a shoe contract with Adidas since the middle of 2019.

Away from the track, he enjoys spending time with his daughter, Anastasia, who will turn 3 later this year. He also serves as an assistant track and field coach at Huron High School in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Like so many U.S. athletes, he is excited about the prospect of competing in the first World Championships to be held on American soil.

“We’re always traveling over to Europe for championships and stuff like that,” he said. “So it’s good to have something here in the U.S. where we get to jump in front of our home crowd. It would be a good feeling for sure.”

He’s not sure how far he can jump, but says he has more in the tank.

Roberts agrees: “I am fairly confident there are very few triple jumpers out there who feel like they have had a perfect jump. Donald is still on that quest for a perfect jump.”