Dynamic duo struck gold in Barcelona

30 years ago, Watts and Young reached track and field pinnacle in the Olympic Games

Three decades ago this weekend, three Los Angeles City Section alumni – Quincy Watts, Kevin Young, and John Smith – stood atop the track and field world.

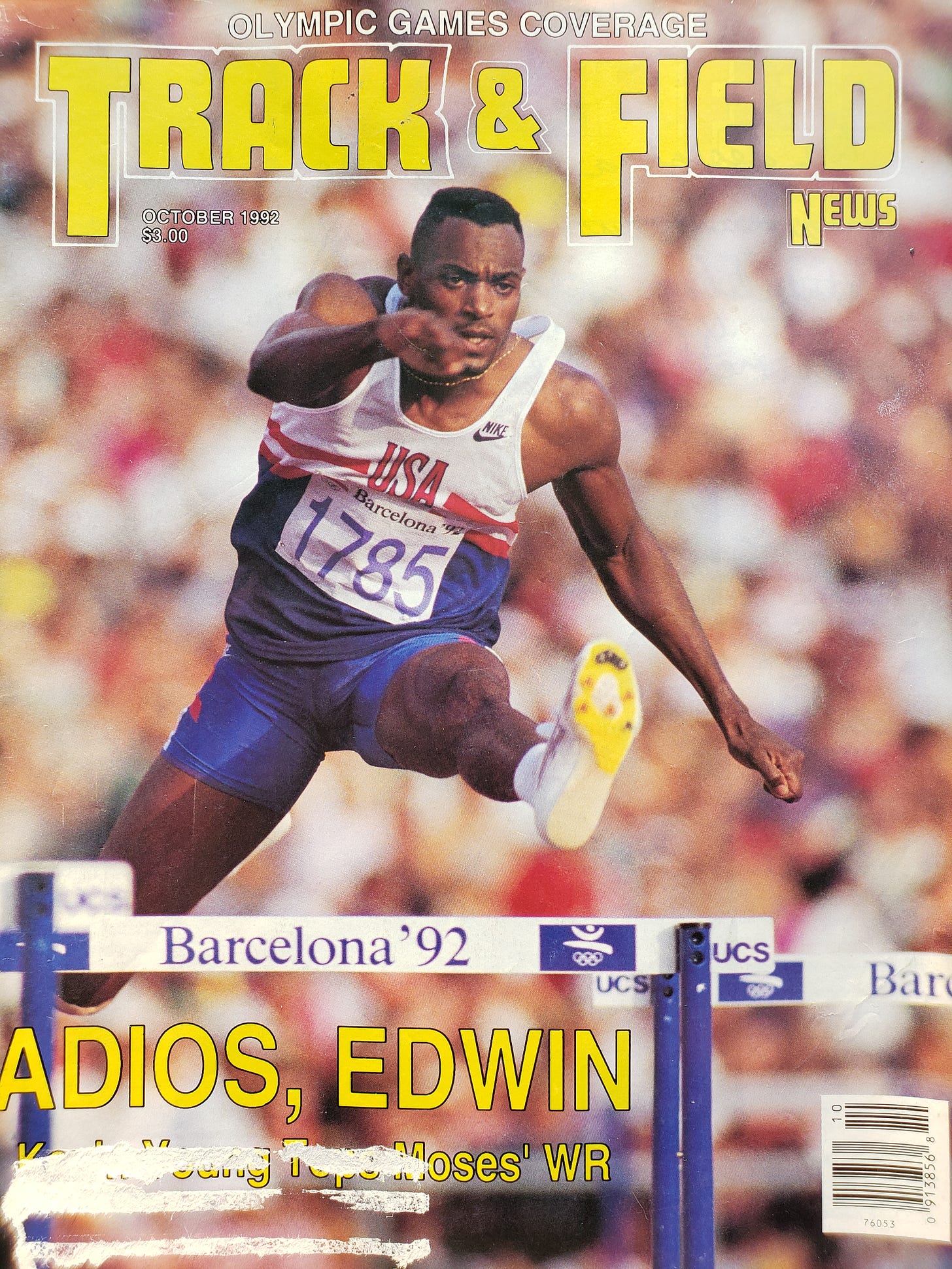

Watts, who had completed his senior season at USC in June of 1992, won the men’s 400-meter dash in the Olympic Games in Barcelona on August 5 with a time of 43.50 seconds, then the second-fastest ever run.

Former UCLA standout Young won the men’s 400 intermediate hurdles the following day with a 46.78 clocking that made him the first man in history to break 47 seconds in the event – a world record that would stand for nearly 29 years.

Smith was the elated coach of both athletes, one – Young – who would be selected as the world male athlete of the year by Track & Field News for 1992, and the other – Watts – who would finish third in that year’s athlete of the year balloting.

“We were ecstatic,” Smith said. “The three of us were ecstatic and extremely proud of what we had accomplished together.”

From the outside, it could have seemed like everything had fallen into place perfectly for the trio. But as Smith likes to point out, there is never a straight line to the top, and Watts and Young were living proof of that.

FROM MOTOWN TO THE VALLEY TO USC

Quincy Watts played basketball for years before he ran in his first track and field meet as an eighth-grade student at Sutter Middle School in Winnetka in Southern California.

The always-tall-for-his-age youngster had lived in Detroit with his mother, Allidah Hunt, for the first 13-plus years of his life, but she asked his father, Rufus Watts, if he would take over the day-to-day rearing of their son when he was in the eighth grade because he was no longer listening to her.

Quincy said he was not a bad kid but admits he was mischievous and running with the wrong crowd.

He and his dad had previously talked about the possibility of Quincy coming to live in Southern California when he was in high school, but those plans got pushed up a semester by his mom’s frustrations with her strong-willed son.

Quincy had never run track before, but a coach at Sutter noticed his talent for sprinting when he set school records in the 50-, 75-, and 100-yard dashes while running on the blacktop.

He remembers how dejected he was after finishing second in his first-ever race – a 100-meter dash – in the 1984 Jesse Owens Games at California State University Los Angeles. But his dad told him there was nothing to be dejected about.

“He said, ‘You did great. You did great,’ “ Quincy said. “He said there was no reason to hang my head. I needed to hold my head high.”

Two years later, Quincy finished second in the 100 and won the 200 in the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) state championships as a sophomore at Taft High School in Woodland Hills, located in the west end of the San Fernando Valley.

Watts ran 10.56 in the 100 and 20.97 in the 200 that season and improved those marks to 10.36 and 20.67 during the 1987 high school season that he capped by winning both events in the state meet. He then ran City Section records of 10.30 and 20.50 – the fastest high school times in the nation that year – while winning age-group titles in the U.S. Junior Olympic championships in Provo, Utah, where the elevation of 4,550 feet – nearly 1,400 meters – aided performances in the sprints, hurdles, and jumps.

The sky seemed to be the limit for the smooth-striding, 6-foot-3 Watts entering the 1988 high school track season, but he strained his right hamstring while running an anchor leg in the 400 relay in a dual meet shortly before the prestigious Arcadia Invitational.

“The incoming runner came up on me and it felt kind of awkward when I got the stick,” Watts said. “And then 30 meters down the track, it just popped.”

The injury – which prevented him from racing for several weeks – would have ended his season under normal circumstances as it would have kept him from running in qualifying meets for the City Section quarterfinals. But section track and field administrators made an exception to the rule, deeming it counter-productive to keep the fastest returning high school sprinter in the nation out of postseason competition when he was close to racing again.

In an effort to lessen the strain on his hamstrings, Watts ran the 400 instead of the 100 upon his return and ended up winning the section title in a personal best of 46.67 – which still ranks sixth on the all-time City Section performer list – and finishing second in the 200, 20.89 to 21.14, to Bryan Bridgewater of Washington High School in Los Angeles.

A victory in the 400 in the state meet would have made Watts the first sprinter ever to win the boys’ 100, 200 and 400 during their career, but he chose to run the 200 in an effort to win an unprecedented third consecutive title in that event.

Although he came up short to Bridgewater again, this time by a margin of 21.00 to 21.02, Watts headed to USC on a track and field scholarship looking forward to a healthy freshman season.

However, his injury woes continued.

He sustained two hamstring injuries during both his freshman and sophomore seasons, and three during the early part of his junior year.

“At that point, I was a mess,” he said. “I was just blowing tires. Left side or right side, I was just blowing tires.”

Watts was so fed up with the injuries that he decided to go out for the USC football team during the fall of his junior year, even though he had never played the sport at a competitive level.

Jim Bush, a future National Track and Field Hall of Famer who had been promoted to an assistant coach at USC in the summer of 1990, approached Watts about the possibility of running the 400 in the spring. But Watts told him he “didn’t want nothing to do with the quarter-mile,” and was going to play football that fall.

Bush, who had coached a slew of outstanding quarter-milers – including two-time NCAA champion Smith – during his head coaching tenure at UCLA from 1964-1984, worried Watts was about to walk away from his track career. But Watts said his dad, who passed away a dozen years ago, told Bush he would be back. That he was just frustrated with the injuries. He wasn’t saying he was giving up on track. He just wanted to try something new.

The truth was, Watts longed to be back in a team environment. As he said, “Track and field is a team sport, but when you’re hurt on the sidelines it’s lonely. It’s pretty lonely and frustrating when you’re hurt, year after year.”

Although Watts never played a down at wide receiver during the 1990 football season, he thrived in the team environment and felt good about how much he had learned and improved as a player by the final game. He came back to track and field with a spark that had been missing. He was even receptive to running the 400 after suffering some hamstring injuries early in the season.

Despite his relative inexperience in the one-lap race, he placed second in the NCAA Championships and had a best of 44.98 that season. He then surprised a lot of people, including himself, by finishing third in The Athletics Congress (TAC) Championships to earn one of three spots for the U.S. team that was going to compete in the World Athletics Championships in Tokyo that summer.

Most athletes would have been thrilled to have that opportunity, but Watts was worn out after a long collegiate season. As he put it, he was ready to end his summer track season and “go back home and be a kid.”

Although he went on to finish fourth in the 400 and run the second leg on the silver-medal winning 1,600-meter relay team in the Pan American Games in Havana in early August, he caught an intestinal bug there and lost 10 pounds.

That initially prompted him to think about hanging up his spikes for the season, but he eventually decided he would opt out of the open 400 in the World Championships, but run in the first round of the 1,600 relay.

He performed so well in a qualifying heat that he earned a spot in the final, when his 43.4 second leg was the third-fastest in history for a U.S. team that finished four-hundredths of a second behind first-place Great Britain’s national record of 2 minutes 57.53 seconds.

His experience in Tokyo was career-changing for Watts.

He came back to USC “one-thousand percent” committed to the 400 and told Bush he would do whatever was asked of him. He also began coming out to the track four mornings a week when he would work – by himself – on his sprinting technique based on video analysis from Dr. Ralph Mann, a biomechanics expert and silver medalist in the intermediate hurdles in the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich.

All the hard work and diligence paid off.

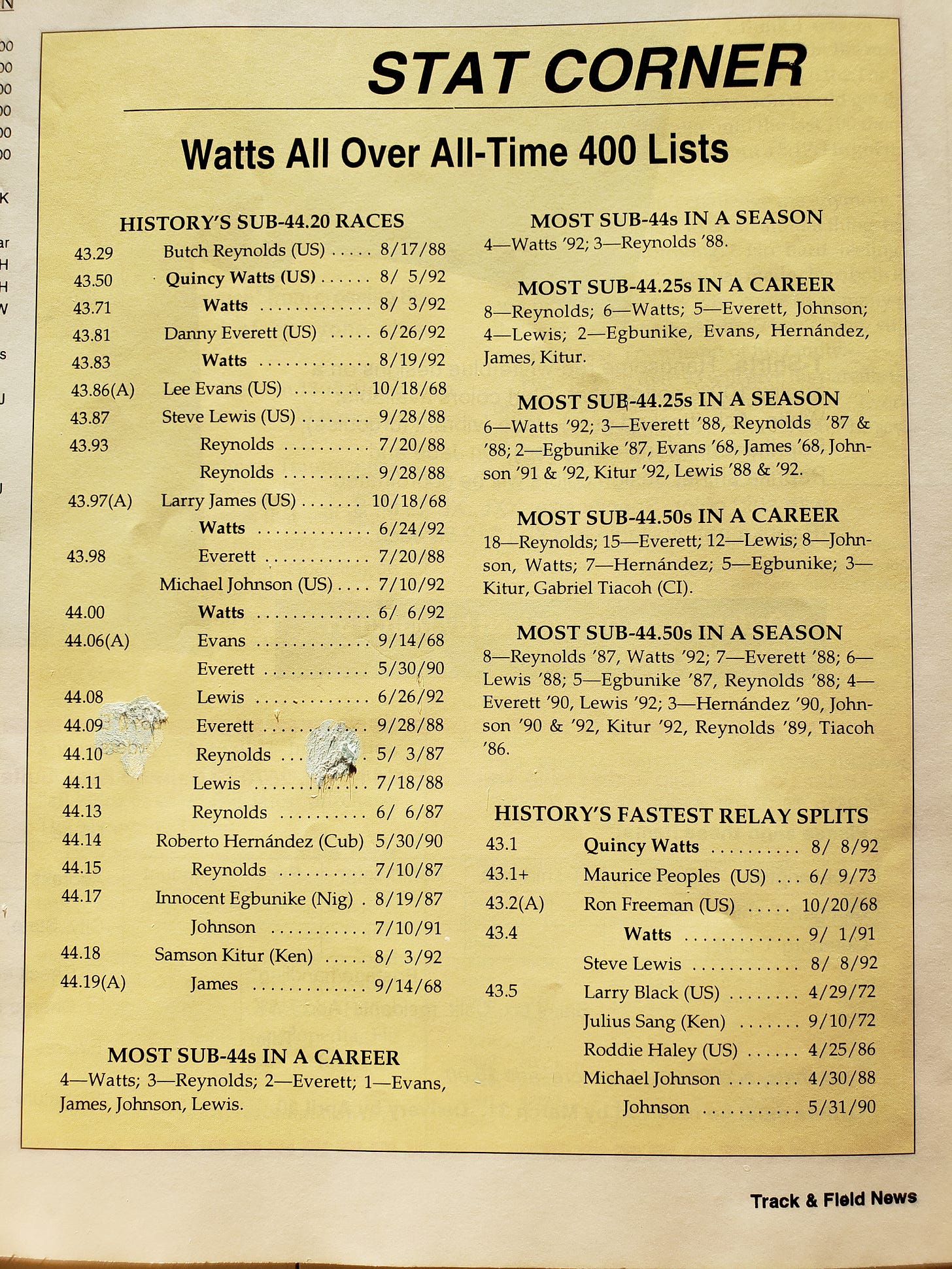

Watts ran a personal best of 44.00 to win the NCAA title on June 6, and he lowered his best to 43.97 in a semifinal of the Olympic Trials on June 24 before running 44.22 in the final two days later to finish third behind 1988 Olympic bronze medalist Danny Everett (43.81) and Olympic champion Steve Lewis (44.08).

The time by Everett, a former L.A. City Section standout for Fairfax High in Los Angeles, was the second fastest in history behind the 43.29 world record set by American Butch Reynolds in 1988. Yet in a feature in the Los Angeles Times before the Olympics, Watts stated that every time he envisioned the final of the 400, he saw himself winning.

He was confident of victory because he had run only two races – winning efforts of 44.99 and 45.60 in Europe in early July – since the Trials and was beginning to feel like himself again after being so fatigued during that qualifying meet in New Orleans that his legs were numb when the runners were called into the set position in the final.

“I knew I just needed to get some rest before the Olympics,” he said. “I had run so many races between the 400, the 4 by 1, and the 4 by 4, in the last month of the collegiate season that I was really tired going into the trials.”

Said Smith, “The trials is not a championship meet. It is a qualifying meet. Which means you just need to finish in the top three.”

FROM WATTS TO WESTWOOD TO WORLD-RECORD HOLDER

Like Quincy Watts, Kevin Young grew up playing basketball – much of it on a nearby playground in the economically disadvantaged Watts neighborhood of South Central Los Angeles.

As the youngest of seven children, Young credits a “sixth sense" he had for avoiding the trouble that he saw engulf some of the kids around him, including an older sister, Carmen, who died in 1990 after being addicted to PCP for many years.

Despite having a very good – but not great – high school track and field career, scholarship offers to NCAA Division I programs were not coming his way after he graduated from Jordan High School in 1984.

Young had bests of 14.23 in the 110-meter high hurdles, 37.54 in the 300 intermediates, and 47 feet 7 inches in the triple jump as a senior. He placed third in the high hurdles in the state championships, but his time in the intermediates – perhaps an indication of things to come – was his best performance in terms of statistics as it tied him for 28th on the national performer list for the year.

Although he excelled in the classroom, he was not accepted to USC, where he had always wanted to go. So when UCLA assistant coach Art Venegas told him the Bruins would love to have him walk-on to the track and field team, he was bound for Westwood.

Once the freshman walk-on arrived, it was Smith – newly hired as a Bruins assistant track and field coach – who recognized Young’s athleticism and versatility through his gangly 6-foot-4 build.

“We liked to call him Spiderman,” Smith said. “He was so athletic and versatile. He could throw the javelin. He could long jump or triple jump off either leg. [Head coach Bob Larsen] was thinking about redshirting him in 1985 and I said he might want to rethink things because Kevin had just done a workout where he ran three 300s in 34 seconds, with a short amount of rest in between them.”

Young’s all-around skills were evident by bests of 13.84 in the high hurdles and 25-4½ in the long jump as a sophomore. Yet Smith zeroed in on his potential in the intermediate hurdles after he ran 51.09 to finish fourth in what was then the Pacific 10 Conference Championships as a freshman.

“I said, ‘You know. You can be as good as Edwin Moses,’ ” Smith said. “He just looked at me like Coach Smith had been drinking a little too much red wine.”

Young’s reaction was understandable. At that time, Moses had set four world records in the intermediates, with a best of 47.02, won Olympic titles in 1976 and ’84, and won the inaugural World Championships meet in 1983. In addition, he had not lost a race since the 1977 season and was in the midst of an unbeaten streak that would last nearly 10 years and include victories in 107 consecutive finals.

Truth be told, Young was still worried about sticking with the team.

“I took up the intermediate hurdles in earnest as a sophomore because we had a lot of good high hurdlers and I wanted to make the team,” Young said. “Making the team was a big concern.”

That worry fell by the wayside during the 1986 collegiate season, which Young capped with a personal best of 48.77 to finish second in the NCAA Championships to 1984 Olympic silver medalist Danny Harris of Iowa State, who set a meet record of 48.33.

Young was the No. 10-ranked intermediate hurdler in the world by Track & Field News for the 1986 season and he would improve to fifth and third in 1987 and ’88, when he won consecutive NCAA titles while also running legs on Bruin quartets that won the 1,600 relay to cap team-title efforts.

He followed his senior collegiate season in 1988 by running a personal best of 47.72 to finish third in the Olympic Trials. He placed fourth in the Olympic Games in Seoul that summer when his 47.94 clocking trailed Andre Phillips of the U.S. (Olympic record of 47.19), Amadou Dia Ba of Senegal (47.23), and the incomparable Moses (47.56).

His 1989 season was not as good as his 1988 campaign in terms of statistics, but he was the top-ranked performer in the world for the first time.

He followed that with No. 6 and 5 rankings in 1990 and ’91 – when he placed fourth in the World Championships – but he was growing impatient with his lack of progress as he began 1992 with a personal best set in 1988.

However, he was undefeated entering the Olympics after winning the Olympic Trials in 47.89 and winning races in Stockholm, Villeneuve d'Ascq, France, and Lausanne, Switzerland, on the European circuit.

He had talked publicly about breaking the 47-second barrier, but admitted recently his No. 1 goal entering the Olympics “was always about getting a medal. It was always about coming out of there with some hardware.”

LET THE GAMES BEGIN

Watts and Young had not known one another until Watts joined Smith’s training group – at the suggestion of Bush – in the summer of 1991. They became friends, despite the fact that Watts was quiet at times and Young loved to talk.

“Q could be more of an introvert,” Smith said of Watts. “While Kevin was talkative and philosophical. He would philosophy with people, even if he didn’t like them.”

Nonetheless, they were roommates in the Olympic Village in Barcelona and what a golden pair they turned out to be.

Watts’ quest for a gold medal in the 400 began smoothly during the morning of Saturday, August 1, when he ran 45.38 to win his first-round qualifying heat. However, things did not go as planned in the quarterfinals during the evening of the following day when Watts finished second in 45.06.

With the top four finishers in each heat advancing to the semifinals the next evening, Watts easily qualified, but he did not feel in rhythm during the race and Smith attributed much of that to the fact that the sunglasses Watts was wearing were slipping off when he came out of the starting blocks and he had to adjust them on the fly.

Smith, a firm believer in the need for elite sprinters to establish their dominance throughout the qualifying process during global title meets, asked to see the sunglasses after the race. When Watts gave them to him, he threw them on the ground and crushed them under his feet. He then gave Watts stern marching orders for his semifinal.

“It is important to win your semifinal,” Smith said. “You need to send a signal. You need to take command and show that if the other competitors want something, they’re going to have to go through you to get it.”

Watts got the message loud and clear as his performance in the second semifinal was spectacular.

Running six hours after Young had timed 48.76 to win his first-round heat in the intermediate hurdles, Watts unleashed a 43.71 clocking to lower the Olympic and collegiate record of 43.86 that American Lee Evans had run in setting a then-world record in the 1968 Games in Mexico City. The time was the second-fastest in history, but the most impressive thing about Watts’ performance might have been the apparent ease in which he ran.

“The first order of business was making the correction from the day before,” he said. “But it just felt great. The race came out easy, John had told me to take a look with a hundred to go to make sure I had my position secured and then gradually shut down. I checked to my right with a hundred to go and didn’t see anyone. I did another check with 75 to go and another with 50 to go. With 30 to go, I realized I’m okay. No one’s here and I kind of shut it down from there.”

Watts’ effort was so superb that Samson Kitur of Kenya, Ian Morris of Trinidad and Tobago, and David Grindley of Great Britain set national records of 44.18, 44.21, and 44.47, respectively, while grabbing the final three qualifying spots. Roger Black of Great Britain, silver medalist in the 1991 World Championships, finished fifth in 44.72 to earn the distinction as the fastest non-qualifier ever.

Everett, who had been dealing with a sore right Achilles’ tendon for much of the season, finished eighth after slowing to a jog, and then a walk, in the final straightaway.

With the final a little more than 49 hours away, Watts isolated himself for much of the next two days underneath the covers in his bed in the Olympic Village with the lights out and the TV on, or in a hotel room he had access to because he was a Nike-affiliated athlete.

“It was nice to have a place where I could just chill out,” he said. “I was in a totally different zone at that moment. The space I was in, the meditative state I was in, I was very in the present. It was a very here and now type of thing and I wouldn’t allow any distractions to come in. I didn’t want to see my father. I didn’t want to see my family. I didn’t want to be outside in the Olympic Village… I just wanted to harness everything I was feeling. I didn’t want to let anything out. I knew I was the Olympic champion and I didn’t want nothing to interfere with that.”

Watts still recalls how his narrowly-focused intensity only allowed for brief conversation as the 400-meter final drew closer and Young came into his room in the Olympic Village. “You ready?” Young asked.

“Yes,” Watts answered. Then silence.

Young said, “I’m going to close the door.”

“Yep.”

About 90 minutes before the final of the men’s 400 on August 5, Young had run a personal best of 47.63 to finish a hundredth of a second behind first-place Winthrop Graham of Jamaica in his semifinal.

Graham, silver medalist in the World Championships, was regarded by many as the gold medal favorite. But Young was very confident about his chances, especially after cruising to his 48.76 clocking in his first-round race two days earlier.

“Damn! I shut down the last 150 and still ran 48.76?” were Young’s first thoughts when he saw the time on the infield video board. “That could have been a sub-47 race if I had run all the way through the finish.”

Watts had no intention of easing up in the final of the 400. Although he was confident of winning, he was wary of defending Olympic champion Lewis, who had upset world-record holder Reynolds in 1988 shortly after completing his freshman season at UCLA.

With Lewis in lane 7 and Watts inside of him in lane 4, Lewis burned the turn and entered the backstretch in the lead. Watts noticed Lewis had gone out faster than usual and said he “had to elevate my race pattern with a little bit more energy than I anticipated and a little earlier than I anticipated. But once I was able to lock into a rhythm, I was like, OK — there’s no turning back now.”

Watts had made up the stagger on Lewis entering the second turn and he came into the home straightaway with a lead of 4-5 meters on his closest pursuer.

“I knew I had the race won coming out of the turn,” he said. “But I wasn’t going to take any chances. With about 50 meters to go. I did something that I usually didn’t do. I went to muscle it. I wanted to give it everything I had and my form kind of went out the window. I just let it all out because I had the great Steve Lewis in the race and I wasn’t gonna look back. I gave it everything I had.”

Watts’ time of 43.50 was the second fastest in history and lowered the Olympic and collegiate record he set two days earlier in the semifinals. Track & Field News declared he “reduced the field behind him to shambles” as his margin of victory over runner-up Lewis (44.21) was the largest in the Olympic Games since Eric Liddell of Great Britain won the 1924 Games in Paris by eight-tenths of a second.

Kitur finished third in 44.24, followed by Morris at 44.25.

“I was thinking this is great, this is awesome,” Watts said about his victory. “Being young, I was looking forward to three or four more Olympics. That was my thought process.”

Watts was also stoked about giving Smith a wonderful 42nd birthday gift as he had said he would.

Less than 23 hours later, Young would give Smith “something even better” in the intermediate hurdles.

Running in lane 4, Young was a lane outside of Graham in 3, and a lane inside of Kriss Akabussi of Great Britain in lane 5.

Graham and Frenchman Stephane Diagana led the field through the first hurdle or two of the 10 flights, but Young began to move at the third hurdle and he was clearly in the lead by the fifth barrier. His advantage expanded as he raced through the second turn. After Graham appeared to have nibbled away a little bit of his lead in the first 20 meters of the home straightaway, Young pumped his arms more vigorously approaching the ninth hurdle and pulled away from his pursuers for the remainder of the race – even despite hitting the 10th hurdle hard with his left lead foot – and raised his right arm in triumph eight meters before the finish line.

Young’s time of 46.78 bested Moses’ 47.02 world record from nine years earlier and left him well ahead of Graham in second (47.66), Akabussi in third (47.82), and Diagana in fourth (48.17).

“After I came off the last hurdle, I knew I was clear of everyone,” Young said. “When you run a race, you can feel who is around you. You can hear them or feel their vibrations on the track, and I could tell there was no one around me. Coming off the last hurdle, I could tell that no one was there… I just started grinning because I knew I was going to win the gold medal.”

The infield clock read 46.79 as Young crossed the finish line and a flashing “Record del Mundo” filled the video screen. The time was amended to the official 46.78 shortly thereafter.

“I was super, super happy,” Young said. “I felt like I had accomplished a lot coming from where I came from. Having grown up in Watts, having been a walk-on at UCLA, having taken up the intermediate hurdles at UCLA because I wanted to make sure I made the team.”

While the intermediate hurdles final ended Young’s Olympic experience, Watts went on to win another gold medal as a member of a U.S. foursome that set a world record of 2:55.74 in the 1,600 relay.

Running the second leg, Watts recorded a scorching 43.1-second split on his carry – the fastest ever at that time – to blow open the race.

For Smith, the victories by Watts and Young were a validation of his coaching.

He had been Lewis’ coach at UCLA when he won the 400 in the 1988 Olympics, but the gold medals won by Watts and Young proved to him that he had not just gotten lucky with Lewis. That he “belonged in the game.”

He was also happy that the dynamic duo had fulfilled their Olympic dreams, for Smith had been “heartbroken” in the 1972 Games in Munich when he had pulled up early in the final of men’s 400 when he re-aggravated an injury to his right hamstring.

Smith had been the No. 1-ranked quarter-miler in the world in 1971 and won the 1972 Olympic Trials, but he injured his hamstring while running in a 200-meter race three weeks before the Games.

THE AFTERMATH

Although Young was the No. 1-ranked intermediate hurdler in the world in 1993 and won the World Championships in Stuttgart, Germany, that summer, Watts came into the next season noticeably heavier and finished fourth in the World Championships in a race in which one of his track spikes literally began to come apart during the second half of the race.

The winner of that race, American Michael Johnson, would go on to win four World and two Olympic titles in the 400, and achieve Olympic immortality in the 1996 Games in Atlanta when he became the first man in history to win the 200 and 400 in the same Olympics, with his 19.32 clocking in the 200 crushing his previous world record of 19.66.

Watts and Young split with Smith following the 1993 season, and their performances tailed off after that.

Watts was the No. 7-ranked 400 sprinter in the world in 1994 and he was ranked ninth in the U.S. in 1995, and 10th in 1996 after finishing seventh in Olympic Trials. But he was never the same after sustaining a back injury in the fall of 1995 when he crashed into a tree after an uninsured motorist clipped his car while trying to pass him on a heavily-traveled road in the Los Angeles area.

Young moved to the Atlanta area after separating from Smith, but he underwent surgery on his left knee in 1995 and his best remaining seasons were in 1996, when he ranked 10th in the U.S., and in 1998, when he ranked eighth.

Watts and Young are both married and they each have three children.

Watts, who lives in Baldwin Hills, has just completed his first season as the director of men’s and women’s track and field and women’s cross-country at USC after being an assistant coach at his alma mater for the previous eight years.

In addition, he coaches Michael Norman, who won the men’s 400 meters in the World Athletics Championships in Eugene, Oregon, last month, and Rai Benjamin, who supplanted Young as the American record-holder in the intermediate hurdles last year and was the silver medalist in the last two World Championships and in the Olympic Games in Tokyo last summer.

Young, who lives in Ebmatingen, a village 20 minutes outside of the Swiss capital of Zurich, is the director of World Record Holdings, LLC, and you can frequently read comments from him in track and field articles about the intermediate hurdles.

Thanks to Karsten Warholm of Norway and Benjamin, Young’s name recognition quotient might have risen in recent years as those two performers closed in on his world record from 1992.

Benjamin came close to breaking the record last year when he ran 46.83 in the Olympic Trials on June 26, and Warholm broke it with a 46.70 clocking on July 1.

A little more than a month later, he crushed that mark with a 45.94 effort in the Olympics on August 3 in a race in which Benjamin finished second in 46.17.

Young was happy for Warholm and his accomplishments. He figured his mark had been “living on borrowed time” since the first decade of this century because hurdlers such as Kerron Clement – best of 47.24 – and Angelo Taylor – 47.25 – were much faster than Young when it came to their bests for 400 meters.

Smith, who had bests of 47.5 in the 440-yard dash and 24-4½ in the long jump as a senior at Fremont High in Los Angeles in 1968, has coached a slew of elite sprinters since the early 1990s, including Olympic and/or World champions Maurice Greene and Carmelita Jeter of the U.S., Marie-Jose’ Perec of France, and Ato Boldon of Trinidad and Tobago.

He is currently working with Michael Cherry of the U.S., who finished fourth in the men’s 400 in the Olympics last year, and Marie-Josee Ta Lou of Ivory Coast, who placed fourth in the women’s 100 and fifth in the 200.

He still loves coaching and gets goose bumps when an athlete he has been working with fully comprehends a concept he has been trying to teach.

When it comes to Watts and Young, he doesn’t dwell on what might have happened had they continued to work with him.

He looks at what occurred as just the way things turned out. That Watts and Young were two very successful athletes who were being pulled in a lot of different directions after their performances in the Olympic Games.

“I don’t look back at what might have been,” Smith said. “I look back at what we accomplished together. I mean, Quincy set a pair of Olympic records in the 400 and won a pair of gold medals. And Kevin won a gold medal and ran a time that stood as the world record until last year. We all had pride in what we did.”

Note - If you enjoyed this story, you can click here to read a 40-year anniversary piece about a mile race in 1982 in which Steve Scott of the U.S. narrowly missed breaking the world record held by Sebastian Coe of Great Britain, and New Zealander John Walker and Irishman Ray Flynn set national records that still stand.

What a great story!